One of the questions I couldn't definitively answer when Printing and Prophecy went to press was what exactly happened to the market for annual astrological prognostic booklets - the Practica teütsch - after 1500. The graph of editions per year starts to decline int the late 1490s, and then it falls dramatically at the end of the century and never reaches its previous height until the late sixteenth century. Here's what the graph looks like grouped by half-decade:

Jonathan Green's research notes on early printing and the language, literature, and culture of medieval and early modern Germany

Friday, March 22, 2013

Friday, March 15, 2013

One-hit wonders of Reformation printing

Among sixteenth-century German printers, many - over 300 - are known from only a single edition. Some of these are accidents of bibliography, where the majority of their careers fall outside of the sixteenth century, or European printers with a single German edition recorded in VD16, but most of them are people whose known career in publishing comprises a single edition. In some cases, like "Degenhard Pfeffinger," printer of VD16 B 8454, one wonders if the name was actually a pseudonym. In other cases, like Andreas Reich, printer of VD16 C 6339, there is simply no more than a single edition.

Friday, March 8, 2013

Alofresant online

I was planning to post on something else that looked interesting, but I was distracted by an online facsimile I hadn't seen yet of "Alofresant," a relatively popular prophecy (18 editions between 1519 and ca. 1540) that Jacques Halbronn suspected originated as propaganda in the disputed imperial election that eventually made Charles V the new Holy Roman Emperor. Curious if there were other facsimiles I had missed, I started looking and found several: of the 18 editions, eight that I know of are now available online. The list appears below.

The thing I was originally planning to post on turned out not to be interesting after all.

The thing I was originally planning to post on turned out not to be interesting after all.

Friday, March 1, 2013

Graphs you haven't seen yet: Martin Luther in print, 1516-1534

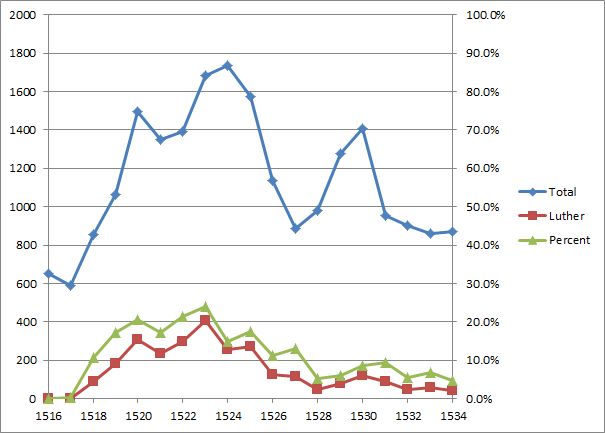

How much of German printing was devoted to the writings of Martin Luther during the early Reformation period? By some estimates, as much as 30% of all titles printed. Can we confirm that estimate?

In theory, it should be simple. We just need to count a) how many total titles are known to VD16 for the relevant years; and b) how many of these titles are Luther's works; and then divide b by a.

We do have to make a few decisions. For a time period to investigate, we'll choose 1516-1534 in order to avoid as many approximately dated works as possible at either end, which are often dated to round decades or half decades. For works, we'll count titles rather than printed volumes (and therefore count compilations as multiple works with possibly different authors).

Here's what we find:

So 30% looks like it might be too high. In the single highest year, 1523, Luther's works reach 24% of the total, which is still a gigantic percentage for one person's works. But over a slightly longer period, 1519-1525, the average is 19%.

But wait! Titles are not the only way to measure books. What about the amount of paper used? How much of the paper that left German presses during the same time period was devoted to works by Luther?

In theory, it should be simple. We just need to know a) the format of all the German books published between 1516 and 1534; and b) the number of leaves in each of these books; and then find the sum of the total leaves multiplied by the inverse of the format. That is, a 10-leaf folio would use 10 * 1/2 = 5 sheets, while a 200-leaf quarto would use 200 * 1/4 = 25 total sheets. As long as we pretend that all paper sheets were the same size (they weren't) and that all editions had the same print run (they didn't), we can come up with a rough, relative measure of the physical output of German printing presses (to be taken with a large measure of salt, but it's the best we can do for now).

Here's what we find:

In terms of paper usage, Luther's works hover around 10% of the total until 1527-28, when they jump up to 20% and 15%, respectively. What stands out here is that the dramatic leap in titles printed between 1517 and 1524 doesn't seem to correspond to a significant rise in paper usage. It looks like existing capacity was used to produce more but shorter works.

The years 1527 and 1528 are noticeably below the trend in paper consumption, while 1529 and 1530 jump significantly above it. Is this normal volatility, bad coding, or something interesting going on in German printing?

Finally, we shouldn't underestimate Luther's effect on German printing, as authors addressing the Reformation in some way comprise a large segment of print production during these years (and during the sixteenth century as a whole). For 1516-1534, here are the top ten authors and a rough count of their editons:

In theory, it should be simple. We just need to count a) how many total titles are known to VD16 for the relevant years; and b) how many of these titles are Luther's works; and then divide b by a.

We do have to make a few decisions. For a time period to investigate, we'll choose 1516-1534 in order to avoid as many approximately dated works as possible at either end, which are often dated to round decades or half decades. For works, we'll count titles rather than printed volumes (and therefore count compilations as multiple works with possibly different authors).

Here's what we find:

So 30% looks like it might be too high. In the single highest year, 1523, Luther's works reach 24% of the total, which is still a gigantic percentage for one person's works. But over a slightly longer period, 1519-1525, the average is 19%.

But wait! Titles are not the only way to measure books. What about the amount of paper used? How much of the paper that left German presses during the same time period was devoted to works by Luther?

In theory, it should be simple. We just need to know a) the format of all the German books published between 1516 and 1534; and b) the number of leaves in each of these books; and then find the sum of the total leaves multiplied by the inverse of the format. That is, a 10-leaf folio would use 10 * 1/2 = 5 sheets, while a 200-leaf quarto would use 200 * 1/4 = 25 total sheets. As long as we pretend that all paper sheets were the same size (they weren't) and that all editions had the same print run (they didn't), we can come up with a rough, relative measure of the physical output of German printing presses (to be taken with a large measure of salt, but it's the best we can do for now).

Here's what we find:

In terms of paper usage, Luther's works hover around 10% of the total until 1527-28, when they jump up to 20% and 15%, respectively. What stands out here is that the dramatic leap in titles printed between 1517 and 1524 doesn't seem to correspond to a significant rise in paper usage. It looks like existing capacity was used to produce more but shorter works.

The years 1527 and 1528 are noticeably below the trend in paper consumption, while 1529 and 1530 jump significantly above it. Is this normal volatility, bad coding, or something interesting going on in German printing?

Finally, we shouldn't underestimate Luther's effect on German printing, as authors addressing the Reformation in some way comprise a large segment of print production during these years (and during the sixteenth century as a whole). For 1516-1534, here are the top ten authors and a rough count of their editons:

- Luther, Martin (2780)

- Erasmus, Desiderius (1284)

- Melanchthon, Philipp (484)

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius (247)

- Rhegius, Urbanus (190)

- Hutten, Ulrich von (161)

- Karlstadt, Andreas (152)

- Bugenhagen, Johannes (146)

- Zwingli, Ulrich (141)

- Eck, Johannes (130)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)